Coopering is the craft of making barrels from wood, and The Coopers Company of Newcastle is one of the oldest of the Incorporated Craft Guilds still active within the City of Newcastle upon Tyne.

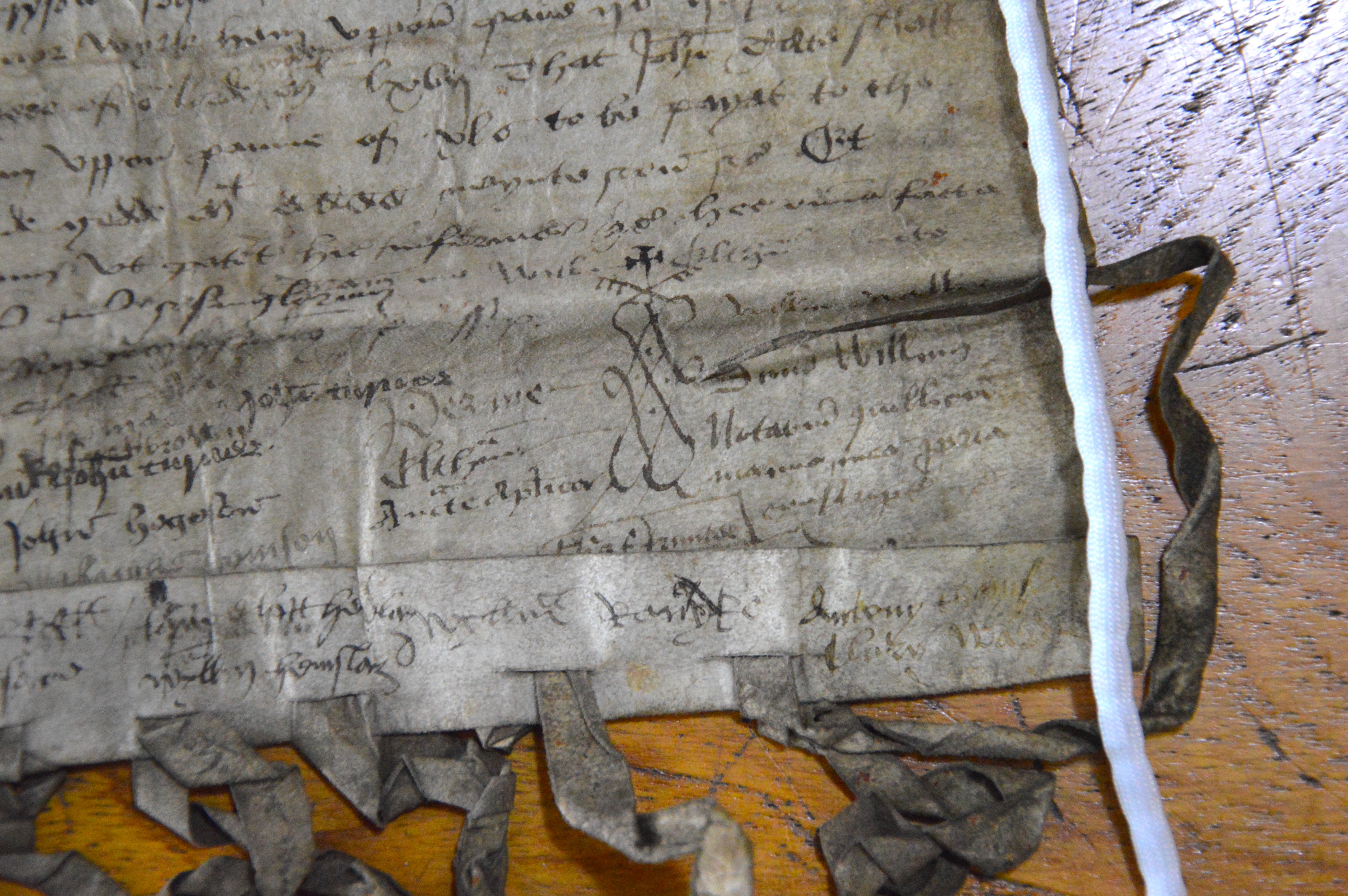

Whilst the date of Incorporation of the Coopers Company is formally listed as 1425, there is substantial evidence to support the idea of Coopers at work within the City Walls long before this date, and almost certainly well into Roman Times.

The Work of the Cooper

Coopering is highly skilled work, which formerly required a long and arduous apprenticeship.

The term Cooper is likely derived from cupa, the Latin word for vat although some claim that it is derived from the Middle Dutch word kupe.

A Cooper makes wooden-staved vessels of a generally cylindrical form, typically where the height is greater than the diameter. The vessel is capped with flattened ends, termed heads, and the structure is bound together with metal hoops, traditionally iron but modern Coopers typically use steel. Examples of a Cooper’s work might include casks, barrels, buckets, tubs, butter churns, hogsheads, firkins, tierces, rundlets, puncheons, pipes, tuns, butts, pins, and breakers.

Tradition has it that, in medieavil times, Coopers would occasioanlly make Coffins although finding documentary evidence of this practice in Newcastle has proven hard to discover. The skill-set required to make a coffin is entirely different although it is possible that certain Coopers had a side-line.

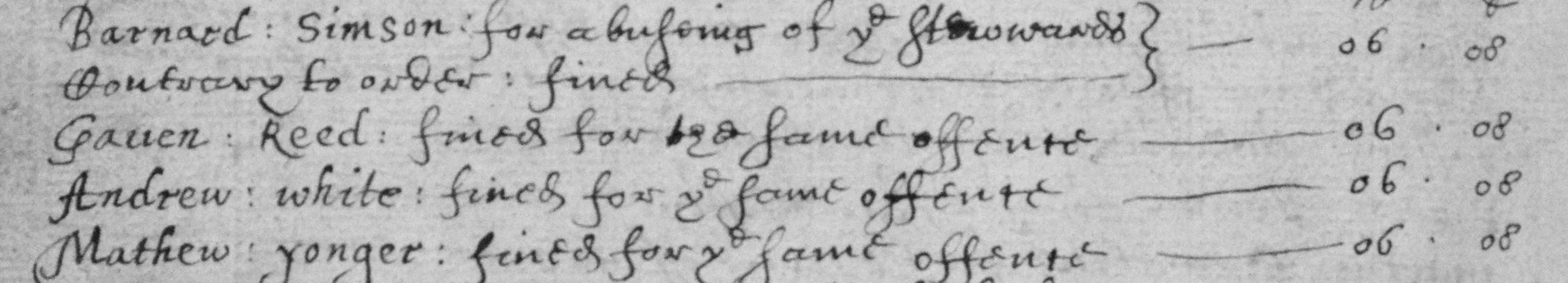

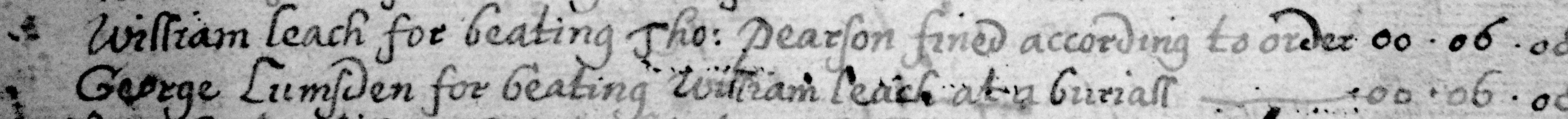

Traditionally, an apprentice Cooper would be expected to begin learning the trade at around the age of seven years. The apprentice would be introduced into the Company and, having been accepted, work under the supervision of an established Master Cooper. He would then spend between six and seven years learning the Coopering trade. Having served his time, his Master and several brothers from the Company of Coopers would examine the apprentice's work and if his work was of the required standard then the Master would arrange to have the apprentice formally admitted to the Company as a Fellow Craftsman. Once given the status of Craftsman, the new Cooper could either remain with the Master at the same Cooperage or leave his service to perhaps either work for another Cooperage or even to establish his own.

Coopering Today

The Coopers Company of the City of Newcastle upon Tyne is highly active in the modern revival of this ancient skill. In recent years, there has been a major upsurge in the demand for new craft beers and whiskeys which rely on wooden caskets for their exceptional taste. Consequently, there has been a major rise in demand for skilled Coopers, particularly in Scotland.

Modern technology, specifically CNC machines, has enabled a new generation of Coopers. It's now possible to produce very high quality, precision barrels in a relatively short space of time and the Coopers of Newcastle are actively researching the techniques required to resurrect this trade.

In Addition, the Coopers of Newcastle have worked hard to develop and maintain strong links both with other Coopering Companies within the United Kingdon and also further abroad. Our stewards regularly travel to meet other Coopering Companies, both socially and on business, to promote Coopering to a wider audience.